Remembering Herbert Minoru Tsuchiya, 1932 - 2023

When he was ten, in 1942, Herb and his family, along with 120,000 other Americans of Japanese ancestry, were forcibly removed from their homes and the Tsuchiya family was sent to the Minidoka War Relocation prison camp in Hunt, Idaho, where they stayed until their release in 1945.

His post-Minidoka path led to graduation from Franklin High School and then the UW School of Pharmacy. In his fifty-year pharmacy career, he was best known as the owner of the Genesee Street Pharmacy in Rainier Valley and for his work as a clinic pharmacy manager at Columbia Health Center Pharmacy and Rainier Park Medical Clinic. He established the Herbert & Bertha Tsuchiya Endowed Student Support Fund for Global Research at the UW to honor his wife, Bertha Chinn Lung Tsuchiya (herself a UW School of Pharmacy graduate). Bertha was a widow with four children when they married; they also had child together.

Herb's professional honors are wide-ranging, including: A.H. Robins/Wyeth Bowl of Hygeia Award; UW Distinguished Alumnus Award for Excellence in Pharmacy Practice; Jitsuo Morikawa Evangelism American Baptist Churches National Award; National Philanthropy Day Outstanding Philanthropic Family Award; and Seattle Mayor's Small Business Award.

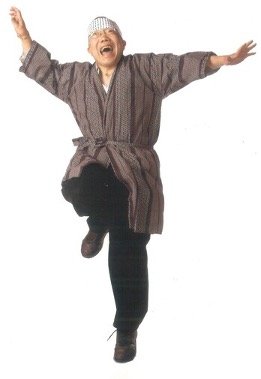

Herbert Minoru Tsuchiya, Photo by Madeline Crowley

He co-founded, with Sam Mitsui, the Walk for Rice for Asian Counseling and Referral (ACRS) in 1990. He explained: “A lot of Asians are lactose intolerant, and the elderly are used to eating whatever they’re used to eating back at home. But a lot of food banks get donations of surplus cheese products and bread. They’re just not used to eating that, so they don’t eat it, give it away or throw it away.” Their first walk raised $2500. From the first walk on Beacon Hill, the annual event moved to Seward Park. In 2008, the walk made $115,000. Since inception the event has raised $1.4 million.

In 2013, Tsuchiya was interviewed for the blogpost ‘People of the Central Area & their Stories,’ portions of which are included below. For the entire interview see here.

What do you remember about the neighborhood (before 1942) when you were sent to the Japanese-American Internment camps?

I remember we were very poor so we lived in a rented a house. It was a diverse neighborhood: Blacks, Jewish, Chinese, Japanese, Filipino. I was the youngest of 7. All my siblings were born at home by midwives. I was the only one who was born in a hospital, at Harborview Medical Center.

Herb's father and sister. Collection Herb Tsuchiya.

One recollection of childhood was that our after-school snack was one slice of Wonder Bread sprinkled with sugar, one slice only. Dinnertime was soup, often salt water with boiled potatoes, carrots, celery, onions and a soup bone, a beef bone that had been gotten from the butcher for free. That bone gave it flavor.

What did your father do?

He worked on the railroad as a gandy-dancer, a laborer. I didn’t learn anything about this ‘til I was an adult. My Dad was trained as a schoolteacher but after the Russian War in Japan there was an economic depression. He was recruited by the railroad to come to America where the streets were paved with gold, where money grows on trees.

Herb;s father at work on the RR. Collection Herb Tsuchiya

This was after the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in America. Since the corporations couldn’t go to China for inexpensive labor anymore they then went to Japan and the Philippines. My father worked in Montana on the Railroad. It was hard labor done by the Chinese, Japanese and Filipino immigrants.

Did your mother work?

She worked as a waitress at a Japanese restaurant on Main Street. She also had to wash our clothes by hand on a washboard with apple soap. We had a hand-crank wringer in a big galvanized tub to get the water out of the clothes.

The big event of the week was to be outside when the Ice Man came so you get free chunks of ice to chew on. We had an icebox in the window with a great big block of ice to cool the food. We didn’t have refrigerators then.

So my mother, as was typical of immigrant families, had to handle everything: childrearing, laundry, cooking, cleaning house and grocery shopping. This on top of having a very authoritative husband who’d say, ‘I worked all day, my meal has to be on time. Where is it?’ (They subsequently moved to the Central Area of Seattle.)

In 1942, you were 10 years old, did you have any real idea of what was happening?

No, not really. All I knew is we had a curfew, we had to be in our house by 8:00pm every night and we were restricted to areas between certain streets. I remember waiting on a street corner for a teacher to bring our report cards from Bailey-Gatzert School. Our teacher made arrangements for us to meet her to get our report cards

Authorities came and checked all our radios to make sure we didn’t have any short wave capabilities and we had to give them any knives or weapons. Our home was one of the pickup points for the bus to take people to the first place of assembly [for internment] at the Puyallup Fairgrounds. People could only bring only two suitcases for their possessions. They’d ask to use our bathroom during the week while they waited. I remember that.

When you came back to the Central Area were you able to return the same place you’d lived before?

When we came back the government gave us $25 to start life all over again. Some of us came back to Seattle but others scattered all over the country. Our family returned to Seattle and were housed at the Seattle Japanese Baptist Church in the Missionary Home. It’s where the Caucasian women missionaries had a place a couple of blocks from the church. We shared living quarters upstairs and a kitchen and a bath and facilities. That was temporary until we could find housing through the Seattle Public Housing Authority for low-income families. Others went to the Japanese Community Center on Weller Avenue off Rainier Avenue. They slept in the classrooms for temporary housing. They called that school space, Hunt Camp, after the mailing address for Minidoka.

So how long before your family found housing of their own?

It was several months before we found housing in the Central Area. We first stayed at Stadium Homes on what is now Martin Luther King Way, which was temporary housing built for the War Workers in industry. Those houses used wood burning stoves for heating and cooking and for heating the hot water, they had pipes that heated the water up – hot water.

After Minidoka did that feel kind of luxurious?

Yes, because these are nice little small homes, little barracks too. Then we moved from there to Rainier Vista housing which as far as we were concerned was even nicer, it was low-income homes on Martin Luther King Ave near Columbian Way.

When you came back how did the Central Area seem to you?

I missed Pioneer Bakery as it was close to our old home. They used alder logs to bake all their goods. As kids we loved to go there on Halloween because we’d get good baked goods for our trick or treating. We loved the aroma of the fresh baked goods.

I was at the old Washington Middle School, then at Franklin High School. For one year after high school I worked at Seattle University as a janitor. So I always thank the Jesuits for providing my tuition to attend the University of Washington, which was very ecumenical of them.

In the book The Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet, the father is a rigid Chinese nationalist because of the war in China. Did you experience in your family that feeling that Japanese and Chinese people should be separate?

Yes, the exceptions were that we had friends that were Chinese and Filipino; it just depended on your friendships. Yet, for the adults there was that tension and that separation. During the post-Pearl Harbor time almost all Chinese wore the button that said, “I am Chinese,” to differentiate themselves because they did not want to be mistaken for Japanese.

When you got older you fell in love with someone of Chinese ancestry?

That resurrected some of the old feelings because my mother was an immigrant from the countryside of Japan and that was a big ‘no-no.’ I was basically marrying an old-time enemy from her point of view. Her standards, her memories and her beliefs were based on her childhood and the conflicts those countries had at that time. I think rural people in every country are more traditional in their beliefs.

So, my mother woke me up in my bedroom when I was still a bachelor and dating… She had a knife at her throat and said, ‘If you keep dating that Chinese woman, I’m going to kill myself.

For my mother who was an original immigrant from Japan it was a big deal. She refused to come to the wedding. But she was counseled by a Taiwanese/Chinese Pastor and friend from the Japanese Congregational Church and he said, ‘You must go to the wedding of your son.’ She reluctantly came.

(Eventually she accepted her.) After our daughter was born, she got to babysit her granddaughter and then everything was ok. Marriage was ok. She got so much joy and happiness.

As you were growing up, did you think about how you were American and yet you were treated differently?

That’s why I became involved in theatre to tell some of these stories to the community, to our own people, to other Americans. So, Breaking the Silence is a readers’ theatre play by Ricky Nogima Louis. She also lived in Minidoka in a block far far from our block. On her 4th birthday, her father was taken by the FBI to be interrogated by the Dept. of Justice in Santa Fe, NM. They had Five Department of Justice (DOJ) camps for single males. These (camps were for) only Buddhist priests, Christian ministers, commercial fisherman with boats, businessmen who went frequently to Japan, and principals, schoolteachers, anyone who was a leader in the community. Immediately after December 7, 1941, (the attack on Pearl Harbor), these individuals were interrogated by the FBI and whisked away to these DOJ camps. Often their families didn’t know where these men, their fathers, were for six months. (Frank Fujii, beloved Franklin art teacher, in his interview with Densho, explained this further. He described that his father “was shifted constantly, from Missoula, Montana, to Bismarck, North Dakota, to Lordsburg, New Mexico, and ended up in Santa Fe, New Mexico.” These four camps were segregated; they were all fathers, separated from their wives. See Quaker Times, Spring 2023).

That’s why I’m motivated to be in this play commissioned by the National Civil Rights group Japanese American Citizens League at their National Convention at the University of Washington 20 years ago. It was for a fundraiser for Gordon Hirabayashi’s legal trial by these young Asian activist lawyers of all nationalities: Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, and Korean who decided to get his conviction overturned.

Gordon Hirabayashi was one of three major dissidents who decided to disobey President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 on the basis that they did not think it was constitutional so they were going to test the constitutionality of it. Gordon was an attorney or student so he intentionally got arrested… He was put into prison. Later, he got three degrees at the University of Washington then he taught mostly in Canada.

Then, 20 years ago at this National Convention we did the play. They had to hold off beginning the play for 20 minutes because Nisei veterans were coming in their wheelchairs, with their walkers and their canes to attend. Some of them cried because of the stories were based on oral histories that the play demonstrated.

So you started breaking the silence not just for yourself but also for your community about 20 years ago when you were about 60 years ago. You held onto those stories until you were about 60. Was there a kind of unspoken pressure to keep those stories quiet? Can you tell me about that?

None of my older sibling would talk about it. That was very common. That was the way the whole Japanese-American community did not talk about the camps and yet it’s what totally defines all of us. We all had that common thread of experience…(In Japan) We don’t deviate from that uniformity. We are quiet, respectful to authority, and we are respectful to elders, to our fathers, mothers and older siblings. We don’t rock the boat. We don’t talk, we internalize, we have ‘gaman,’ patience, perseverance persistence in spite of suffering and pain. I always kid the mentorees I counsel that pain and suffering are good for building character.