The Geology and Early History of Rainier Valley

Submitted by Barbara Mahoney, ‘67

Dodging traffic, watching for pedestrians and bikers, and stopping at too many stoplights while admiring the Mt. Rainier view, can make a trip down Rainier Avenue perilous and not leave us time to think about the geology of the area. What formed the valley over the millennia?

Franklin High School, 1913. Franklin was originally a two-year school located in the building later occupied by Washington Junior High School. In 1912 Franklin moved to its present site and became a four-year school. Photo was taken from Beacon Hill.

Rainier Valley is not an old stream bed, though it looks like it could be. As romantic and idyllic a beautiful tree-lined river running through the rocks for millions of years sounds, the formation of the valley was much more dramatic and violent. The primary forces were earthquakes, dramatic uplifts, volcanic activity, and destructive and life-giving glaciers.

Human-made geologic changes included the reorientation of the Duwamish River in 1913 to straighten it for commerce and the lowering of the level of Lake Washington for the Ship Canal, which was started at about the same time and made the Rainer Valley dry enough for increased agriculture.

Beacon Hill and Capitol Hill were once one long ridge until engineers sluiced away what is now the north end of Beacon Hill to connect the valley with downtown in the early 1900s. Removed materials were sent to what is now Boeing Field and the SODO areas.

During these excavations and work at the Denny Regrade, it was discovered that the city lies on debris from the Ice Age’s Vashon Glacier till that covers the city’s bedrock with up to 3,700 feet of sand, gravel, and clay. The only place where bedrock is exposed is from Seward Park west to Beacon Hill. On Beacon Hill this rock dives steeply underground like a mountainside. The bedrock is so thick that a person standing at its thickest point on Beacon Hill weighs slightly more than they would at a northern thinner spot due to a higher gravitational force.

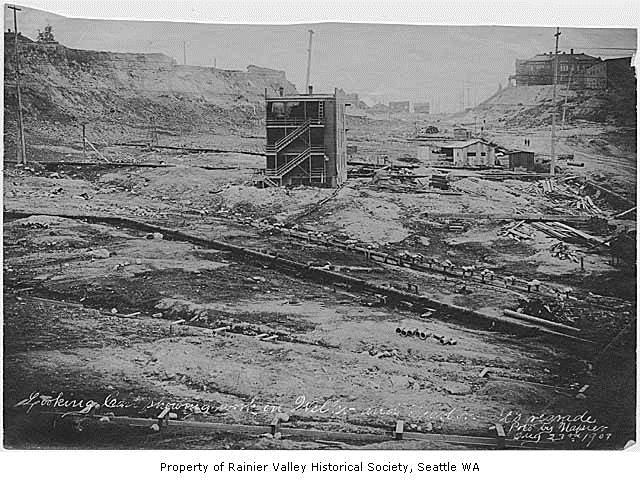

Looking east, showing work on Weller and Dearborn Street’s regrade. In 1909 a regrade of Dearborn Street removed more than a million cubic yards of earth. This reconstruction greatly improved access between downtown and Rainier Valley. Property of Rainier Valley Historical Society, Seattle, WA

Glaciers did not cross what is now the Canadian/Washington border until about 19,000 years ago, the start of the Vashon Glaciation. During this time the glacier’s Puget Lobe advanced at a rate of about 443 feet per year, reaching Seattle about 17,950 ago. Around 16,950 years ago the Puget Lobe reached its final extent around Tenino. By 16,150 years ago, the retreat reached Seattle, depositing huge amounts of till and shaping the modern version of the city and Puget Sound.

Seventeen thousand years ago, a massive glacier the height of five Space Needles covered what is now Seattle and a large part of western Washington. (Courtesy of the Burke Museum)

Animals and plant life flourished during the Vashon Glaciation. Though most of the animals are now extinct, much of the plant life continues to thrive. Bison, camels, musk oxen, dire wolves, scimitar cats, American lions, saber-toothed tigers, mammoths, mastodons, and sloths lived among the pine, spruce, hemlock, and alders.

Before the Ice Ages, the Puget Sound region was formed by the gigantic forces caused by the movement of intersecting tectonic plates creating subduction (where one plate dives beneath its neighboring plate). Smaller crustal fault zones and volcanoes have formed the hardscape of the entire Northwest including Seattle. Uplift, folding, and faulting are responsible for the formation of the city’s many north-to-south running hills including Beacon Hill and Mount Baker, with their steep sides and narrow Rainier Valley running for seven miles between.

Indigenous People of Rainier Valley

The early indigenous peoples inhabiting Rainier Valley prior to 1879 (when the first Europeans arrived) referred to themselves as “Lake People,” or Xacua’bs (hah-chu-AHBSH), a branch of the Duwamish tribe that settled along the shores of Lake Washington. The Duwamish are part of the Southern Puget Sound branch of the Coast Salish Indian people. Their winter camps of cedar longhouses along the Lake Washington shore formed a series of smaller villages with the main village located in present-day Renton where the Cedar River entered the lake. The longhouses were as wide as fifty feet and several hundred feet long housing extended families of twenty to twenty-five individuals. During summer months, the families left their winter homes and lived in portable huts made from cattails.

Original Duwamish longhouse. (duwamishtribe.org)

Camps were located at Bryn Mawr, such-TEE-chib (wading place), Brighton Beach, hah-HOA-hlch (forbidden place), and at Pritchard Island TLEELH-chus (little island). Women married outside the tribe in a practice called exogamy which helped develop relationships between tribes and reduce conflict.

The Lake People traveled a trail through Rainier Valley from Pioneer Square to Renton along what is now approximately Rainier and Renton Avenues. They were a fishing, hunting, and gathering people who may have used the area around Genesee Park to dry their catch. It is believed that their primary burial site was in Renton with perhaps a secondary site at what is now the Columbia City Library.

The Treaty of Point Elliott, of which the Duwamish (Dxwdew?abs) Tribal Chief Si’ahl (Chief Seattle) was a primary signatory, was signed as a government-to-government document in 1855. The treaty guaranteed a reservation, and hunting and fishing rights. The Duwamish Tribe turned over 54,000 acres of their homeland including the cities of Renton, Seattle, Tukwila, Bellevue, and Mercer Island and much of King County. The European-Americans soon violated the treaty and fomented Indian-on-Indian battles.

The only known photo of Chief Seattle. (Courtesy Seattle PI)

In 1866 Thomas Paige, US Indian Agent, recommended a reservation be established for the Duwamish. However, the European immigrants petitioned against a reservation near Seattle. Arthur Denny and others, with a notable hypocrisy, protested that “such a reservation would be a great injustice” and that the promised reservation would be “of little value to the Indians.” The protest petition prevailed and the reservation was blocked. The Duwamish were to receive nothing.

The 1855 treaty recognized the Duwamish as a tribe, but 123 years later, in 1978, Department of Indian Affairs amended the treaty by adding new onerous requirements to achieving acknowledgment. By this time large numbers of Duwamish tribal members had already allied with other regional recognized tribes, to gain the benefits promised under the treaty, such as healthcare, self -regulation, self-determination, and land.

A hat belonging to Angeline, Chief Seattle’s daughter, in the Duwamish Longhouse Museum.

On January 19, 2001, the final day of the Clinton administration, the Duwamish were officially recognized as a tribal organization. One day later, on the first day of the Bush administration, the acknowledgment went under “review” and was subsequently manipulated by both political authorities and other tribes, causing it to be sent through the courts. In the end, the court determined that the 1978 amended requirements had not been fully met by the Duwamish.

Despite these numerous rejections, today’s Duwamish Tribal members hold close their distinctive traditions of home life, language (Lushootseed), oral history, stories, foods, potlatches, canoe building and use, basketry, carving, medicines, and song and dance.

Present day Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center. (duwamishtribe.org)

The beautiful cedar Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center located on traditional land (4705 West Marginal Way SW, phone 206 431 1582, duwamishtribe.org) personifies their message “We Are Still Here.” The Longhouse features a lovingly curated museum and gift shop with a large meeting room for cultural experiences and exchanges that can be rented by non-tribal organizations.